The Rise of Mushrooms

For the last decade the mushroom’s popularity has slowly been rising, culminating in a recent burst of mainstream content and scientific research.

The cute innocence as well as profound power of our often button capped friend is broadcasted by brands, bookshops have dedicated mushroom sections, and streaming sites are firing out movies and docuseries about fungi’s abilities and benefits.

Scientists are praising the healing powers of fungi for humans and the Earth, while experimental studies of magic mushrooms are popping up in every part of the globe. But this hasn’t always been the case.

Source: YAWN

NOT QUITE CUTE ENOUGH

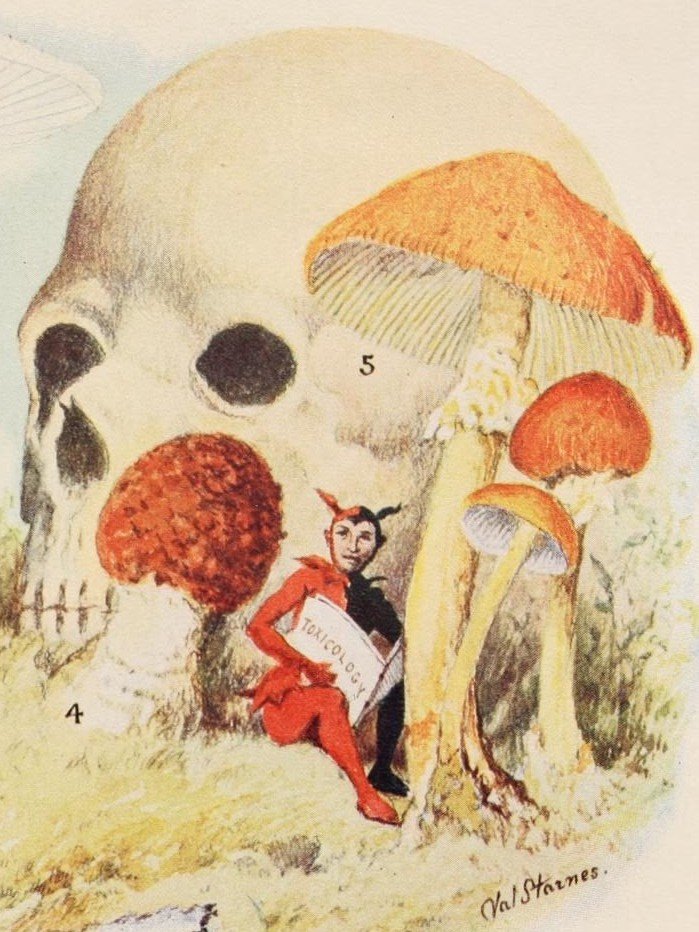

Mushrooms, and more broadly fungi – the microorganisms responsible for mushrooms as well as things like yeast and mould – have been historically associated with disease, death, and decay in the Western psyche. Mould is linked to allergic and asthmatic diseases. Poisonous mushrooms have long been an evil trope in myths. Fungi disassemble organic material like dead animal bodies and wood. This has all helped create an aversion to fungi.

On top of that, small hard to see parts of the kingdoms of life tend to take a back seat to the more preferred large or charismatic creatures. Those that create a sense of empathy build interest and resources into the fight for their preservation.

Partly as a result, conservation efforts have overlooked fungi. While the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species has almost completely assessed groups like amphibians, birds, and mammals, less than 1% of fungi species have been assessed.

However, there’s a growing wave of supporters fighting for the recognition and preservation of this seemingly small creature.

FIGHTING FOR FUNGI

In 2012 Chile became the first government globally to include fungi in environmental legislation, but a decade later few institutions directly contain fungi in their policy frameworks. Last year a new campaign was launched by some leading environmental groups - which includes IUCN’s Species Survival Commission - calling on state leaders to create protections for fungi under international, regional, and domestic law and policy.

“Although fungi underpin life on Earth, they have been overlooked and under-appreciated, and largely excluded from conservation strategies and environmental laws,” said the group.

Various organisations have been popping up across the globe to educate people on how fungi are critical to protecting and restoring Earth, ensure their integration into conservation strategies, and recognise them as one of the three kingdoms of life - particularly through using ‘mycologically inclusive language’ by adding ‘fungi’ to ‘flora and fauna’.

Clearly momentum is building behind this kingdom of life, so what’s changed?

THE GREAT CONNECTORS

As we begin to experience the adverse impacts of climate change, the importance and possibilities of fungi are becoming more obvious. They help regulate atmospheric carbon dioxide, such as through sequestering huge amounts of carbon through root symbiosis with plants. While as decomposers they clean polluted soils, support mammal digestion, and the global nutrient cycle.

All of these abilities – and more – are related to fungi being the Earth’s ultimate community makers. Fungi are what make forests, woodlands and grasslands interconnected ecosystems - instead of individual competing plants – by enabling them to communicate, cooperate and compromise.

In the 2020 book ‘Entangled Life’ Merlin Sheldrake articulates just how important their community creation is to our world.

“[Without] fungal webs no plant would exist anywhere. All life on land, including my own, depend on these networks,” writes Sheldrake.

He explains how some of the major events on Earth are thanks to the communal relationship’s fungi create. Fungi served as plants root systems until they could evolve their own and make it out of water 500 million years ago. Now over 90% of plants rely on mycorrhiza, a symbiotic association between fungus and plant that links trees in shared networks.

Fungi’s ability to connect is not only vital to Earth but offers inspiration for transformation and renewal through community during times of despair. Biodiversity decline caused by individual greed and pandemic induced isolation has made us confront our disconnect from the web of life and appreciate the importance of community.

SHIFTING PERSPECTIVES

The seeds of this new cultural shift towards connection were planted in the early 2000’s and can be seen in the recent history of humans using mushrooms. The 2019 documentary ‘Fantastic Fungi’ shows this history, beginning with the accidental discovery of penicillin in a mouldy petri dish in 1928, then focusing on the 1960s psilocybin - the psychoactive compound that hundreds of fungi species produce – studies into its potential benefits for mental health.

Self Portrait by Louise Bourgois

This research was banned in the 1970’s due to the culture wars that encompassed alternative communities psychedelic drug use and their connection to free love and anti-war campaigning. The 1970’s-90’s marked a period of ‘greed is good’ that put individual corporate success on a pedestal and disregarded the environmental and social costs.

The end of the 1990’s begun an era building towards sustainability through shared commitments only reachable through communication, cooperation, and compromise. This new era saw the fungi research bans lifted in the early 2000’s and funding begun to trickle in.

HEALING HUMANS

Now, an explosion of studies shows the possibilities of fungi for human use. Growing evidence indicates mushrooms like Reishi and Turkey Tail may help fight cancer and memory loss. While new research suggests that the hominin evolution - in which the human brain made an inexplicable leap - may be thanks in part to ingesting psilocybin.

The potential benefits of magic mushrooms for mental health are particularly evident. Journalist Michael Pollan’s 2018 book ‘How to Change Your Mind’ – now also a docuseries - explores these studies and experiences, showing how psychedelic drugs like psilocybin and LSD can be therapeutic for those facing depression, addiction, and death.

How To Change Your Mind doco, source Netflix

However, results of these studies are often significantly whitewashed, with one paper finding that over 80% of participants in contemporary clinical trials of psychedelics are white. The exclusion and co-opting of magic mushroom use has been a common and ongoing theme.

CO-OPTED CONNECTION

Magic mushrooms have long been considered sacred by the Indigenous Mazatec in Mexico, but the power of plant medicine was suppressed by the Catholic church when the country was colonised 400 years ago. Now, the growing popularity of magic mushrooms has meant that groups that have historically oppressed the healing power of Nature have caught on and appropriated their use.

Mazatec Mushroom Stones 1000 B.C. to 500 A.D.

Groups focused on consumerism such as Gwyneth Paltrow’s ‘Goop’ – a business built around mainstreaming fringe health practices while being primarily orientated around wealth and its trappings – advocate for magic mushroom retreats, often costing tens of thousands of dollars. While those most in need of treatments remain stuck behind red tape.

The concept of purchasing personal inner healing at inaccessible luxury villas seems at odds with fungi, which revolve around relationship interdependency, adaptation, and cooperation. This appropriation is indicative of how the West places importance on the individual, instead of connectedness with Nature including other humans.

While the individual experience of mushrooms may be prioritised for some, the incredibly effective survival technique of connection is the lesson most seem to be taking from the resurgence of mushrooms.

COMMUNITY THROUGH PRECARITY

One interesting take on the value of mushrooms in teaching connection is the 2016 book ‘The Mushroom at the End of the World’. Anthropologist Anna Tsing applies lessons from each uncertain stage of the coveted Matsutake mushrooms relationship with humans to our world’s current state of precarity.

“Precarity means not being able to plan. But it also stimulates noticing, as one works with what is available. To live well with others, we need to use all our senses, even if it means feeling around in the duff,” writes Tsing.

Portrait of Anna Tsing, source: Tank Magazine

This is particularly true for realising the symbiotic relationship we have with nature. Tsing writes how woodland revitalization groups, “hope that small-scale disturbance might draw both people and forests out of alienation, building a world of overlapping lifeways in which mutualistic transformation, the mode of mycorrhiza, might yet be possible.”

Adding humans, animals and all things living to mycorrhiza helps explain how observance, understanding and mutual support is needed to live in harmony with Nature and ourselves.

Clearly fungi offer not only important solutions but also inspiration to renew community with humans and Nature, and there’s still so much left to discover. The rise of the mushroom is well deserved and long overdue, so let’s learn from this inconspicuous genius.